Tracking down energetic cosmic rays

Once in a while, nature runs experiments that no human lab can match. Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays are a good example.

Cosmic rays are fast, high energy particles from space that strike Earth’s atmosphere with energies far beyond what even the most powerful particle accelerators can routinely create. Most particles are the nuclei of atoms such as hydrogen or helium and a smaller fraction are electrons.

When a cosmic-ray particle hits the atmosphere, it triggers a large ‘shower’ of particles spread over many square-kilometres. (One such shower may have caused a serious error in a computer onboard an Airbus A320 aircraft on October 30, causing it to suddenly drop 100 feet, injuring several people onboard.) By observing and measuring these showers, scientists hope to probe two big questions at once: what kinds of cosmic events accelerate matter to such extreme energies, and what happens to particle interactions at energies we can’t otherwise test.

The Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina is one of the world’s main instruments for this work. Its latest results, published in Physical Review Letters on December 9, focus on a curiously simple idea: does the energy spectrum of these cosmic rays — i.e. how many particles arrive at each energy — look the same from every direction of the sky?

In the new study, the Pierre Auger Collaboration analysed data with three notable features. First, the Observatory recorded the spectrum above 2.5 EeV. One EeV is 1018 electron-volt (eV), a unit of energy applied to subatomic particles. Second, it recorded this spectrum across a wide declination range, from +44.8º to −90º. In this range, +90º is the celestial north pole and –90º is the celestial south pole. And third, the analysis included around 3.1 lakh events collected between 2004 and 2022.

The direction in which a cosmic ray is coming from carries information about its origins. If, say, a handful of galaxies or starburst regions are responsible for the highest energy cosmic rays, then the spectrum should show a bump in that part from the sky, and nowhere else.

Understanding the direction from which the most powerful cosmic rays come has become more important since the Collaboration found evidence before that these directions aren’t perfectly uniform. Above 8 EeV, for instance, the Observatory has reported a modest but clear imbalance across the sky. It has also sensed a similarly modest link between extremely energetic cosmic rays and specific parts of space.

Against this backdrop, the new study is part of a larger effort to elevate ultra-high-energy cosmic rays from a curiosity into a way to map the location of ‘cosmic accelerators’ in the nearby universe.

This is like the trajectory that neutrino astronomy has taken as well. For much of the 20th century, neutrinos frustrated physicists because they knew the particles were the universe’s second-most abundant, yet they remain extremely difficult to catch and study. Because neutrinos carry no electric charge and interact only weakly with matter, they pass through stars and magnetic fields almost untouched, making them unusually honest witnesses to violent places in the universe. However, physicists could take advantage of that only if they could build suitable detectors. And step by step that’s what happened. Today, experiments like IceCube in Antarctica realise neutrino astronomy: a way to study the universe using neutrinos. (Francis Halzen’s long push for this detector is why he’s been awarded the APS Medal for 2026.)

Cosmic rays stand on the cusp of a similar opportunity. To this end, the Pierre Auger Collaboration had to find whether the spectrum is dependent or independent of direction. A direction-independent spectrum would push the field towards models in which different types of cosmic sources produce high-energy cosmic rays; a direction-dependent spectrum would do the opposite.

The new result was firm: across declinations from −90° to +44.8°, the team didn’t find a meaningful change in the spectrum’s shape.

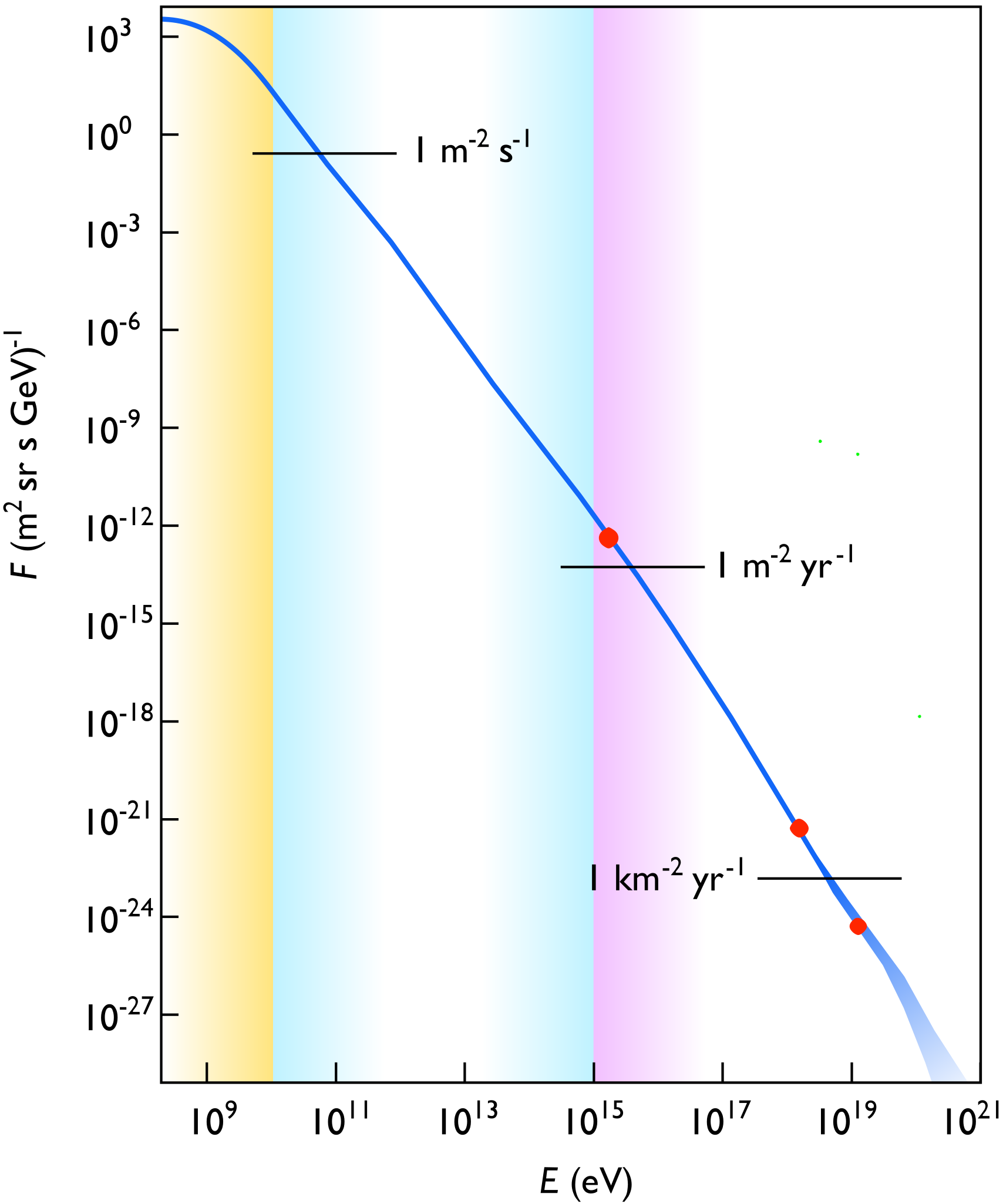

Cosmic ray researchers read the energy spectrum as a sort of forensic record. Over many decades, experiments have shown that the spectrum doesn’t increase smoothly. If you plotted the energy on the graph, in other words, you wouldn’t see a smooth curve. Instead you’d see the curve bending and changing how steep it is in places (see image below). These bumps reflect changes in the sources of cosmic rays, in the chemical makeup of the particles (protons v. nuclei), and how cosmic rays lose energy as they travel intergalactic space before reaching Earth.

The Collaboration’s new paper framed its findings in the context of two recent developments.

First, above 8 EeV, cosmic rays aren’t arriving in perfectly random directions around Earth. Instead roughly one half of the sky supplies 6% more such cosmic rays. Physicists have interpreted this to mean the distribution is being shaped by large-scale structure in the nearby universe, by magnetic fields or by both.

Second, the Collaboration previously identified evidence for an ‘instep’ feature near 10 EeV.

If you look at the energy curve (shown above), you’ll notice a shift in slope at three points. Top to bottom, they’re called the ‘knee’, the ‘ankle’, and the ‘instep’. At each of these points, physicists believe, the set of physical effects producing the cosmic rays changes.

(LHAASO, a large detector array in China built to catch the particle showers made by very energetic gamma rays, recently reported signs that microquasar jets — where a stellar-mass black hole pulls in gas from a companion star and emits fast beams of radiation — could be accelerating cosmic rays to near the knee part of the spectrum.)

A spectrum whose shape changes depending on the direction is a way to connect these two aspects. If the instep is due to a small number of nearby, unusually strong sources, you might expect it to show up more strongly in the part of the sky where those sources are located. If the instep is a generic feature produced by many broadly similar sources, it should appear in essentially the same way across the sky (after accounting for the modest unevenness of the dipole). In the new study, the Collaboration tried to make that distinction sharper.

The Pierre Auger Observatory detects showers of particles in the atmosphere with an array of water tanks spread over a large area. Showers arriving near-vertically and those arriving at an angle closer to the horizon behave differently because Earth’s magnetic field distorts their paths. So the analysis used different methods to reconstruct the cosmic rays based on their showers for angles up to 60º (vertical) and from 60º to 80º (inclined). Scientists inferred the energy in the rays based on the properties of the particles in the shower.

In the declination range −90º and +44.8º, the Observatory found the spectrum didn’t vary significantly with declination, with or without the dipole. In other words, once the Collaboration accounted for the disuniform intensity in the sky, the spectrum’s shape didn’t change depending on the direction.

The second major result was the ‘instep’, with the findings reinforcing previous evidence for this feature.

Now, if the instep was mainly caused by a small number of nearby sources, it would be reasonable to expect the spectrum would change depending on the declination. But the study found the spectrum to be indistinguishable across declinations. This in turn, per the Collaboration, disfavours the possibility of a small number of nearby sources contributing ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. Instead, the spectrum’s key features could be set by many sources and/or effects acting together.

The paper also suggested that the spectrum steepening near the instep could be due to a change in what the cosmic rays are made of: from lighter nuclei like helium to heavier nuclei like carbon and oxygen. If this bend in the curve is really due to a change in the cosmic rays’ composition, rather than in their sources, then cosmic rays coming from all directions should have this feature. And this is what the Pierre Auger Collaboration has reported: the spectrum’s shape doesn’t change by direction.

According to the paper’s authors, because the spectrum looks the same in different parts of the sky, the next clues to cracking the mystery of cosmic rays’ origins need to come from tests that measure their composition more clearly, helping to explain the instep.